By John Czarzasty and David Bustoz

Hohokam villages at the foot of South Mountain in Phoenix, Arizona specialized in the production of large jars for market exchange during the pre-Classic period. In the Classic period these communities specialized in the manufacture of polished red ware bowls and jars. Excavations at Las Canopas, a large Hohokam village in Phoenix occupied from the late Pioneer period through the Classic period, have uncovered evidence of a kiln. The evidence consists of structural form, size, the presence of a substantial oxidation ring and copious ashy refuse, location on the fringe of the village, and spatially associated hand tools used for pottery manufacture. The kiln may have been built as the direct result of increased demand for pottery production at Las Canopas for market exchange in the pre-Classic period, and may have been a technological response to demand for not just more vessels but also the larger vessels used for exchange.

Durante el período preclásico los habitantes de las aldeas Hohokam, ubicadas al pie de South Mountain en Phoenix, Arizona, se enfocaron en la producción de grandes jarras para el intercambio mercantil. En el período clásico, los residentes de estas comunidades se especializaron en la fabricación de cajetes y jarras de loza roja pulida. En las excavaciones en Las Canopas en Phoenix, ocupado desde finales del período pionero hasta el clásico, se ha encontrado evidencia de un horno ubicado en las afueras de este pueblo grande. La evidencia consiste en una forma estructural de gran tamaño, notándose la presencia de un círculo de oxidación, abundante ceniza y herramientas de alfarería. El horno tal vez fue construido en respuesta al aumento de la demanda por cerámica para intercambiar, siendo un avance tecnológico para aumentar la cantidad y tamaño de las vasijas producidas en Las Canopas durante el período preclásico.

We thank the many people who helped bring this article into being. Foremost among them is Erik Steinbach, who excavated the kiln. Dusty Rice did the graphics work presented herein. Kristin Sullivan translated the abstract into Spanish. We’d also like to thank the editors of Kiva. Although we couldn’t close the deal and were unsuccessful in getting the article published in Kiva, their encouragement is greatly appreciated. And to the two anonymous reviews that provided their comments on the article during the unsuccessful Kiva submission, we are sincerely grateful.

Evidence for physical locations of Hohokam pottery manufacture is scant. For decades, the only convincing evidence for on-site pottery making in the Hohokam area had come from Snaketown, where Haury (1976) identified “kilns” in association with clay mixing basins. Just after the turn of this century, on-site pottery making in the Hohokam area has also been reported at the Sweetwater site on the Gila River Indian Community (Harry 2000). Recent excavations at Las Canopas, a large Hohokam village in the metropolitan Phoenix area occupied from the Colonial period through the Classic period, have uncovered evidence of a kiln and associated pottery-manufacturing hand tools.

Evidence for on-site manufacture of pottery includes features such as kilns and clay mixing pits, hand tools associated with preparation of vessels, and raw clay (Sullivan 1988; Harry 2005). (See Crown [1981:363] for a contrary opinion regarding hand tools.) Kojo (1996:330) suggests that the localized presence of such items and features is “solid evidence” for the presence of ceramic production.

A kiln is a formal structure in which prepared clay pottery is fired. Kilns offer better control of the firing process than surface firing of pottery. Kilns can deliver higher temperatures than bonfires, and they offer better control over the oxygen content of the burning atmosphere. The use of a kiln may reflect a potter’s full-time status and greater technological expertise compared to a potter who uses surface firing (Kramer 1985:81).

Prior to excavations at Las Canopas, the only convincing evidence for on-site pottery making in the Hohokam area has been from Snaketown, a Sedentary period Hohokam site. Haury (1976:194) excavated several features related to pottery manufacture: clay mixing basins and “pit kilns.” The pit kilns were circular features up to 1 meter in depth, with the largest reaching 3 meters in diameter. However, the artifactual record indicating pottery manufacture at Snaketown is, to use Haury’s (1976:197) words, “disappointingly slim.” Haury (1976:194) concluded, based on “stylistic diversity,” that pottery manufacture at Snaketown was a household industry, though he acknowledged the trend towards mass production. The presence of pit kilns supports the supposition of such a trend.

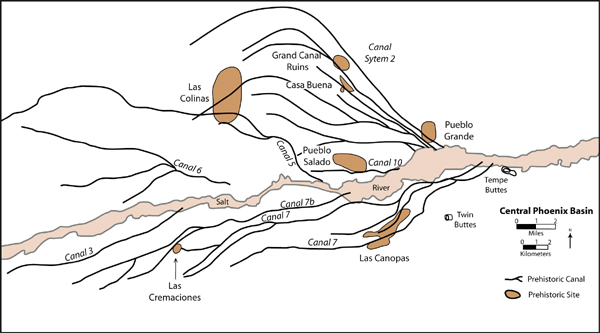

The excavations in the Cottonwood Locus of Las Canopas, AZ T:12:137 (ASM), were conducted by (RSA) Salado Archaeology in the summer and fall of 2005 on two parcels of private land totaling 20.7 acres (Czarzasty and Rice 2007). Las Canopas was a major Hohokam ball court and platform mound center on Canal 7 of the Salt River Basin (Figure 1), and was occupied at least as early as the Snaketown phase (A.D. 700) continuing through the Civano Phase (A.D. 1450). The excavations uncovered a kiln (Feature 1045). Additional evidence for pottery manufacture at Las Canopas includes clay mixing pits and an assortment of hand tools associated with pottery manufacture.

Figure 1. Las Canopas and nearby Hohokam sites in the Phoenix Basin.

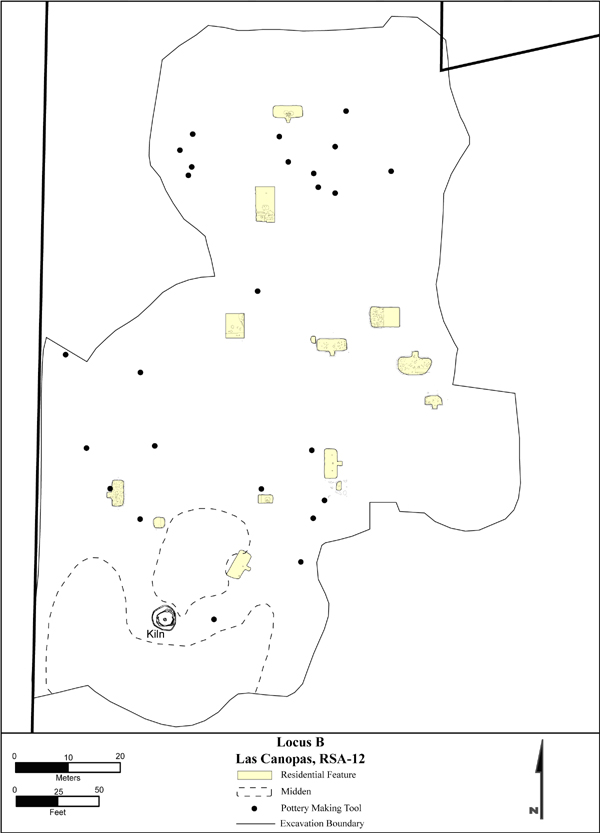

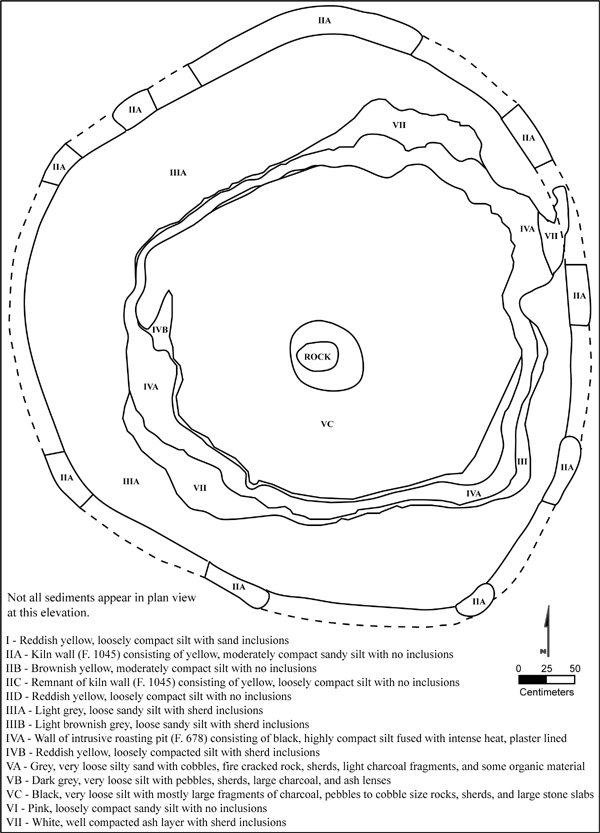

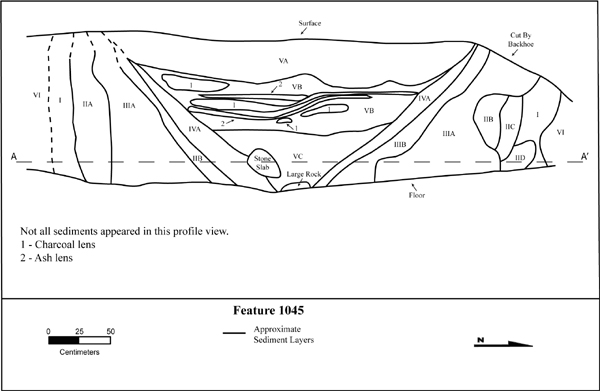

Feature 1045 in Locus B of the RSA excavation (Figure 2) of the Cottonwood Locus at Las Canopas is a kiln. Inserted later within the kiln, perhaps due to the ease with which the ash contents could be excavated, was Feature 678, a roasting pit or horno. Feature 1045 is a large, ash-filled circular pit, approximately 4.7 meters wide by at least 2 meters deep (Figures 3 and 4). The border of the pit was an oxidation ring (sediments IIA-C, Figures 3 and 4) approximately 30 cm thick. Historic farming activities at the site would have removed any existing above ground elements of Features 678 and 1045.

Feature 1045 was initially thought to be midden deposits surrounding Feature 678 that had oxidized in a way that caused the appearance of two features. However, on examination of the layer of ashy midden material (IIIA) surrounding the horno, it was found to differ from the oxidized soil forming the boundary of Feature 1045 and present in Strata I and II (A,B,C) in contact with it. Stratum I is the non-oxidized sandy silt that is common to the non-midden areas in Locus B. Strata IIA, B, and C seem to represent an oxidized rind of a larger feature and Stratum IIIA represents subsequent ashy midden fill, complete with sherd inclusions, deposited after the thermal events that oxidized Stata IIA, B, and C. Strata IIA, B, and C are compositionally dissimilar from the surrounding sediments and are not likely to have been deposited naturally, which argues for their being part of a thermal feature older than the horno (Figure 5).

Figure 2. Locus B, RSA Excavations at Las Canopas, AZ T:12:137 (ASM).

Figure 3. Plan View of Kiln (Feature 1045) and Intrusive Horno (Feature 678) at Depth of A-A’ Cut in Figure 4 below, Las Caopas, AZ T:12:137 (ASM).

Figure 4. Profile View of Kiln (Feature 1045) and Intrusive Horno (Feature 678), Las Caopas, AZ T:12;137 (ASM) (See Figure 3 above for sediment descriptions).

Figure 5. Feature 678 (Horno) within Feature 1045 (Kiln).

It has been proposed that Feature 1045 was a pottery kiln for the following reasons. First, there is the form and size of the feature. Las Canopas and other villages at the foot of South Mountain specialized in the production of large jars for market exchange in the pre-Classic period (Abbott 2000:202-208). The feature is roughly cylindrical, and its size makes it suitable for production of large jars. Second, the thick oxidized ring of encircling ash is indicative of high temperature combustion within the feature. The ash within the feature was very fine and ubiquitous in the midden surrounding the feature (Figure 2). An extensive ashy midden is what one would expect to see as a result of a large wood-fueled kiln working over an extended period of time. Third, the feature is located on the outskirts of the Cottonwood Locus at Las Canopas, on the edge of the residence area (Figure 2). Kramer (1985:81) has found it commonplace for pottery production facilities to be located away from residential areas to “minimize the annoyance caused by smoke.”

Finally, excavations at Las Canopas recovered 33 artifacts associated with pottery manufacture, 26 of which were in Locus B as was the kiln. One of the pottery anvils is shown in Figure 6, and a polishing stone is shown in Figure 7. Approximately 80% of the artifacts came from Locus B (Table 1). Excavation was conducted using backhoes for surface scraping down to a depth of approximately 1.5 meter across the entire excavation area delineated in Figure 2. The artifacts found during this excavation present a spatial pattern spreading outward from the kiln into the residential part of the site in Locus B only.

Las Canopas and other villages at the foot of South Mountain specialized in the production of large jars for market exchange in the pre-Classic period, and in the Classic period communities in the same area specialized in the manufacture of polished red ware bowls and jars (Abbott 2000:212). Based on structural form, size, a substantial oxidation ring, copious ashy refuse, location on the fringe of the village, and spatially associated hand tools used for pottery manufacture, Feature 1045 is believed to have been a kiln. The kiln may have been a response to increased demand for pottery production at Las Canopas for pottery for market exchange in the pre-Classic period. Feature 1045 may have been the technological response needed to fire not just more vessels but also the larger vessels used for exchange. After Feature 1045 was no longer in use, perhaps due to the contraction of the exchange system during the Classic period (Abbott 2003:211-213), an horno (Feature 678) was dug into its upper portion. The creators of Feature 678 benefited from the looseness of the ashy fill of the kiln in relation to its fire-hardened outer surface while digging the horno into the kiln, and they continued to benefit from the feature’s location on the periphery of the village, minimizing nuisance from smoke.

Figure 6. Pottery Anvil from Locus B, Las Canopas.

| Artifact Type | Count |

|---|---|

| Groundstone - polishing stone | 10 |

| Groundstone - anvil | 16 |

| Raw clay | 1 |

Figure 7. Polishing Stone from Locus B, Las Canopas.

Abbott, D.

2000 Ceramics and Community Organization among the Hohokam. University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

2003 Centuries of Decline during the Hohokam Classic Period at Pueblo Grande. University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Crown, P.L.

1981 Variability in Ceramic Manufacture at the Chodistaas Site, East-Central Arizona. Ph.D. dissertation. University of Arizona. University Microfilms, Ann Arbor.

Czarzasty, John L., and Glen E. Rice

2009 Excavations at Las Canopas: A Hohokam Village in the Phoenix Basin. Pueblo Grande Museum Anthropological Papers No.17. Pueblo Grande Museum, Phoenix, Arizona.

Harry, Karen G.

2000 Community-based Craft Specialization: The West Branch Site. In Hohokam Village Revisited, edited by D. E. Doyel, S. K. Fish, and P. R. Fish, pp.197-220. Southwestern and Rocky Mountain Division, American Association for the Advancement of Science, Fort Collins, Colorado.

2005 Ceramic Specialization and Agricultural Marginality: Do Ethnographic Models Expalin the Development of Specialized Pottery Production in the American Southwest? American Antiquity 70:295-320.

Haury, Emil W.

1976 The Hohokam: Desert Farmers and Craftsmen: Excavations at Snaketown, 1964- 1965. University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Kojo, Yasushi

1996 Production of Prehistoric Southwestern Ceramics: A Low-Technology Approach. In American Antiquity 61(2):325-339.

Kramer, C.

1985 Ceramic Ethnoarchaeology. In Annual Review of Anthropology, vol.14, edited by B.J. Siegel. Pp. 77-102. Annual Reviews, Palo Alto, California.

Sullivan, Alan P., III

1988 Prehistoric Southwestern Ceramic Manufacture: The Limitations of Current Evidence. In American Antiquity 53:23-35.